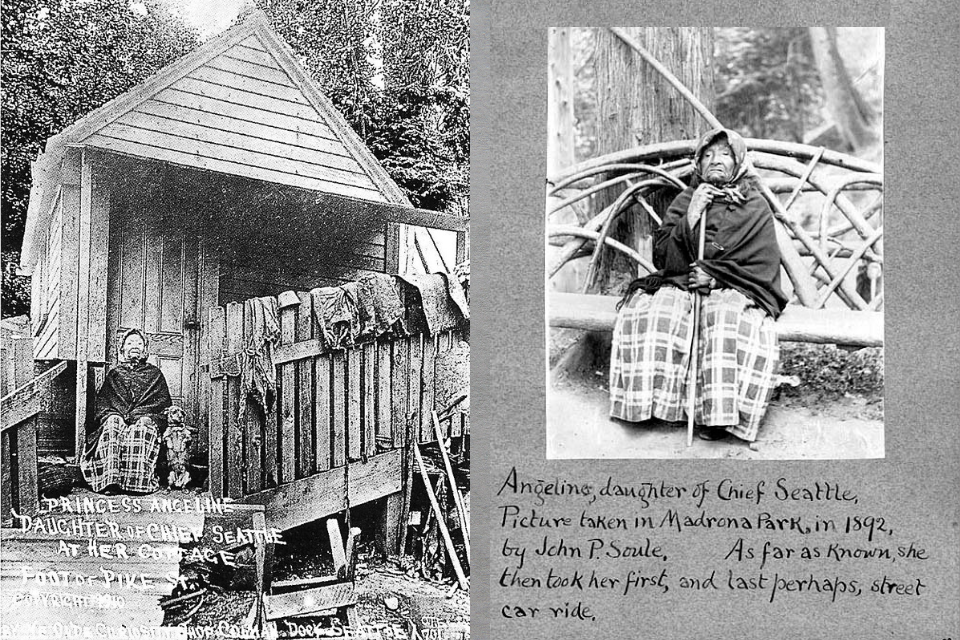

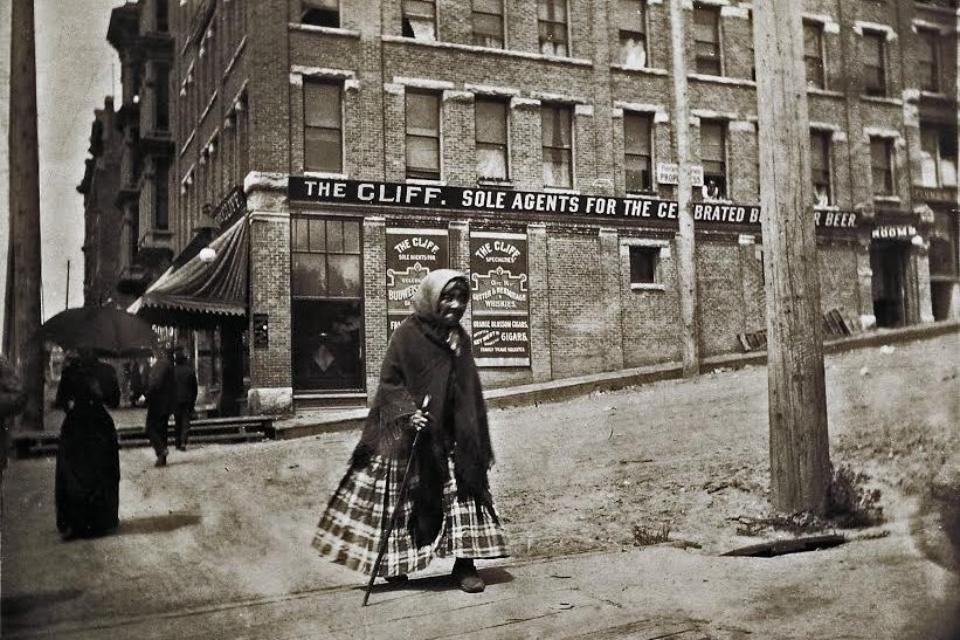

More commonly known as Princess Angeline, Kikisoblu was the daughter of Chief Seattle, our city’s namesake, yet her story is often overlooked in Seattle’s long history.

How Kikisoblu became a Princess

Born in the 1820s, Kikisoblu was the oldest daughter of Chief Si'ahl (later Anglicized to "Chief Seattle"), leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes. She bore witness to the rise of pioneers traveling west to settle on Indigenous land, and she befriended many of Seattle’s founding families. Catherine Maynard, a pioneer woman from one of these founding families, was said to have thought Kikisoblu should have a name that reflected her status as a chief’s daughter and gave her the title “Princess Angeline” – a name which Angeline used and others continue to use today.

Despite her friendship with these settlers, conflict between Indigenous people and the government continued to grow, ultimately leading to the Treaty of Point Elliott. Signed in 1855 by representatives from many local tribes, including Chief Seattle, this treaty promised to establish reservations for tribes who signed it and guaranteed fishing and hunting rights to their people. In exchange, said tribes would cede all rights to their land – millions of acres of it – to the United States Government.

Unfortunately, these rights were not upheld for all tribes, and some settlers even went out of their way to protest the treaty’s promise. Outraged letters were sent to Congress claiming that a reservation near their flourishing settlement would injure its growth, and these reservations would be “of little value to the Indians” anyway.

Over 150 years after this treaty was signed, there are currently 574 federally recognized tribes across the United States and 29 within Washington State, but hundreds more remain unrecognized across the country. As a result, these tribes face issues with housing, healthcare, and education due to lack of federal funding and support. Insufficient resources, inefficient federal program delivery, and historically discriminatory practices all contribute to the cycle of poverty, poor education, and poor health many Native Americans face; particularly those living on reservations who faced even more challenges during the pandemic.

As a result of the Treaty of Point Elliott, many Indigenous peoples were forced out of their ancestral lands to make room for more white settlers, but Princess Angeline refused to leave.

Although she was now considered an illegal resident in her own homeland, Princess Angeline was determined to remain where she lived, a small cabin on the waterfront near what is now Pike Place Market. She washed laundry, sold handwoven baskets, and allowed photographers to take her picture for a dollar. One of these photographers was Edward Sheriff Curtis, and after having Princess Angeline as his first model and inspiration, he went on to document Native American life across the United States (pre-colonization) through photographs.

Princess Angeline died in 1896 on May 31, and Seattle residents honored her final wishes by burying her in a canoe-shaped coffin. She was laid to rest in Lake View Cemetery in Capitol Hill amongst many of her pioneer friends.

Honoring Princess Angeline

Princess Angeline’s kindness, bravery, and tenacity is still celebrated today, and our Angeline's Day Center for Women is named in honor of her, and is coincidentally located in Belltown, an area Princess Angeline frequented. We see her same resilience and determination in the people we serve, and we want to help them find housing stability and security just like she did.

Angeline’s Day Center provides safety and support for women experiencing homelessness. Our drop-in services include meals, laundry, showers, lockers, and connections to community resources and services for housing, employment, and stability.

Learn how you can help support the women we serve by donating to our Winter Warmth Drive, and visit our Angeline’s Day Center page to see what other donation items we currently need.

Ana Rodriguez-Knutsen is the Content Specialist for YWCA's Marketing & Editorial team. From fiction writing to advocacy, Ana works with an intersectional mindset to uplift and amplify the voices of underrepresented communities.

We share the stories of our program participants, programs, and staff, as well as news about the agency and what’s happening in our King and Snohomish community.